As ‘unacceptable’ rates of birth trauma are revealed across NSW by a landmark government inquiry, Catherine Lewis investigates the reasons behind this perturbing pattern – and what steps are being taken to boost maternity care across the state.

“All that matters is a healthy baby.’ We hear that all too often but I don’t agree. A healthy mum, physically and emotionally, matters too,” says Sydney birth coach, Damaris Lee. One in three Australian women suffers from physical and/or psychological birth trauma before, during or after their baby is born, says the Australasian Birth Trauma Association. It’s an experience so wounding it can cause ‘lasting negative impacts on lives,’ while highlighting a health system that is falling far short of the standard of care that women deserve.

The record 4,000 submissions to the NSW Government’s 2024 Birth Trauma Inquiry found that one in 10 women – 95 per cent of whom give birth in hospitals or birth centres, with 79 per cent as public patients – had suffered obstetric violence. That is, any act that harms a pregnant, birthing or postpartum woman, such as non-consensual examinations, coercing, failing to give pain relief or making a woman feel powerless. “The personal stories shared revealed systemic issues that must be urgently addressed, and the unprecedented scale of evidence received reflects the number of birthing parents unnecessarily traumatised giving birth,” says Emma Hurst MP, Chair of the Select Committee on Birth Trauma.

Birth trauma is subjective. A birth that is classed as ‘straightforward,’ in medical terms and results in a healthy baby, will often be deemed a success, but a woman can feel very differently. “Trauma can result from not only what happens during birth, but also how you feel as a result of your experience,” says Damaris Lee, former midwife-turned doula (birth coach) and founder of Mum’s Oasis, which supports mums-to-be through birth and beyond. “Maybe your midwife said everything went fine, but that doesn’t mean it was fine for you. You don’t need permission from the medical staff to define your birth experience as traumatic. If your birth felt traumatic for you, it was.”

Easier to quantify is the physical – the perineal tears or pelvic floor damage. While the psychological – postnatal depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress or obsessive-compulsive disorder – can leach the colour from blissful baby days long-term, if left untreated. “More women than previously realised suffer silently from severe pelvic floor damage, perineal injuries and PTSD symptoms…that are embarrassing and difficult to explain and result in…reduced quality of life and decreased infant bonding,” says Elizabeth Skinner, founder of Sydney’s Birth Trauma Consultancy. Even midwives, emotionally invested at the highest peaks and lowest valleys of life, amidst a punishing schedule and a skeleton staff, can suffer Secondary Traumatic Stress following a difficult birth.

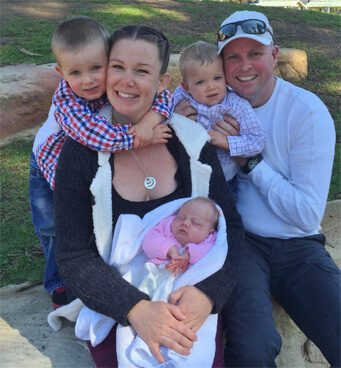

Karen McFadden had a positive birthing experiences with her three children at North Sydney’s Mater Hospital

“Every birth must be met with dignity, respect and compassion.” Emma Hurst, chair of the Select Committee on Birth Trauma

Fear of trauma has sparked record numbers of caesareans, up from 29.8 per cent in 2018, to 33.6 in public hospitals and 43.9 to 49.4 per cent in private, of which 40 per cent are elective – says NSW Health’s annual Mothers and Babies report, with the increasing age of women giving birth in NSW also playing a part. In the Northern Sydney health district, one of the most affluent parts of the state and home to the highest number of new mothers aged over 35, almost double are opting for elective caesareans, compared to those in more regional areas.

But Hannah Dahlen, from Western Sydney University’s School of Nursing and Midwifery, warns that rising rates of surgery are sparking concern amongst clinicians due to potential long-term health impacts. “There is mounting scientific evidence which suggests that children born by spontaneous vaginal birth, without commonly used medical and surgical intervention, have fewer health problems,” she says. Women who have caesareans may face longer recovery times and have less chance of a normal vaginal birth in future.

Placing women ‘at the centre’ of their own care is behind NSW Government commitments to support 42 of the trauma inquiry’s 43 recommendations for maternity care improvements, says Health Minister Ryan Park. “We have heard what matters most to women and their families… and our ongoing commitment and actions will improve their experiences,” he says. Continuity of care, where the same midwife or team supports a mother throughout pregnancy and child birth, and informed consent improvements are two priorities to be fast-tracked over the coming year.

But the reality is less continuity, more cuts, says the NSW Nurses and Midwives Association, warning that rumoured maternity staffing cuts across the state will ‘compromise patient care.’ While Australia has seen record number of births in recent years – spiking post-pandemic with 315,000 – the number of midwives has slumped by more than 1,220, says NSW Health, with the National Skills Commission warning of shortages in every state and territory. “Midwives strive to deliver the best possible care to women and babies in a system that has been chronically understaffed, under-resourced and neglected. This cannot continue any longer and the NSW Government must urgently act to stem the loss of midwives,” warns midwives association assistant general secretary Michael Whaites.

Enter a $2.5 billion cash injection over four years in the 2023/24 NSW budget, to recruit and retain more skilled nurses and midwives. This includes $419 million to recruit an additional 1,200 by 2026 in public hospitals. Other plans include greater investment in mental health support, post-partum services and trauma-informed care, as well as increased funding for psychological support for those experiencing pregnancy loss, within separate spaces in public hospitals. The $376 million Brighter Beginnings service will assist children and their families during the ‘crucial’ first 2,000 days, from pregnancy to school, while the $6 million Pregnancy Connect service will boost access to specialist care for complicated pregnancies.

Damaris Lee

“The NSW Government must urgently act to stem the loss of midwives.” Michael Whaites, NSW Nurses and Midwives Association

Royal North Shore Hospital’s maternity antenatal postnatal service, (MAPS) allocates a named midwife to each woman attending midwifery clinic, to provide coordinated pregnancy and postnatal care. Following discharge from hospital, the MAPS midwife makes home visits under the midwifery in the home model of care, allowing women to build relationships. This can boost birth outcomes and midwife satisfaction in providing continuity of care. “We know birth trauma is avoidable and preventable and we’ll continue to advocate for universal access to midwifery-led continuity of care, as we know these models provide the best outcomes for women,” agrees NSW Midwives Association’s Mr Whaites.

Emma Hurst

Mother-of-three, Karen McFadden, had just such a positive birthing experience at North Sydney’s private Mater Hospital, which welcomes more than 2,500 babies each year. “The same wonderful midwife, Wendy, delivered my first and second sons and made us feel like we were part of the family,” Karen tells North Shore Living. “Yes, the facilities are first class, but it’s the calm, kind and genuine staff that make it an outstanding place to give birth. I went into labour with my second child, Archie, six weeks early and my obstetrician calmly laid out a clear plan to allow him to be able to breathe unassisted once he was born. We were absolutely terrified, but the staff were so supportive and reassuring, that we felt safe and optimistic that everything would be fine – and it was.”

While shining a spotlight on areas ripe for improvement across local and state-wide maternity care, as the trauma inquiry has done, will make a dent, until staff shortages are solved, the health system will continue to labour under the strain. Ensuring midwives have the support and capacity to tailor care to the vastly differing needs of each woman must become inherent practice if the trauma trend is to be reversed. As Emma Hurst MP says, “Every birth must be met with dignity, respect and compassion.”